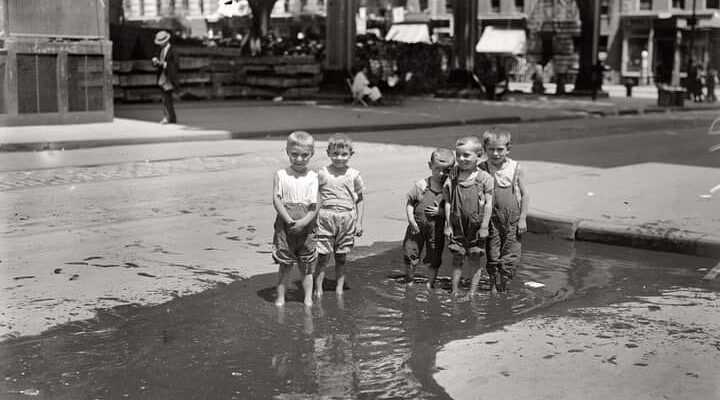

In 1913 over 12,000 children were arrested in New York City for playing. Many kids devoted themselves to healthful natural play, despite the fact that they were playing in what one 1913 newspaper called the most dangerous and degrading playground in the world, the streets of New York City. At the time, NYC streets were filled with cars, horse drawn carts, push carts, and street cars. Because a child’s main option was to play in or near the street, hundreds of children on a monthly basis were killed, maimed, and injured due to the terrible street conditions. The main issue that was not being addressed by the local government was that these kids lived in New York City, with an estimated 700,000 children citywide, and there were very few if any safe and welcoming places for children to play freely.

Back then, like today, kids loved to play classic games like jacks, follow the leader, and hopscotch, but the game played more than any other game was baseball. In one census taken from 120,000 children in 1913 over 1,500 girls were playing baseball alongside the boys.

New Yorkers knew that something needed to change. The arrests and the deaths of children were not the best optics for New York politics. In 1914 the newspaper, “The Evening World” led by journalist Sophie Irene Loeb began to advocate weekly through the newspaper for safer and more friendly play spaces for children. She used her newspaper column, which was gaining influence, to by reach out and to gain support of wealthy New York City mothers, the Police Commissioner Arthur Woods, and finally by getting the green light from the 95th Mayor (1914-1917) New York City Mayor John Purroy Mitchel.

“The possibilities of this play movement cannot be underestimated. It opens up so many avenues by which the little children from all walks of life will prove to be an asset rather than a liability to our community.” -Sophie Irene Loeb

The other play advocacy group leading the way in New York City was The People’s Institute, spearheaded by John Collier and Edward R. Barrows. It was these men on April 27, 1913 in a New York Times article, who began to reimagine the role of play with children in New York City. They proposed the idea of “Play Streets for children” as a safe and healthy alternative to the horrific situation on the streets.

“Close off certain streets for certain hours. It need not always be the same street. The children will follow the shifting of streets which may be necessary in a given neighborhood.” -John Collier

On July 25,1914, two years after Collier’s vision casting, the first Play Street was piloted led by the authority and leadership of Police Commissioner Arthur Woods. The first Play Street took place on Eldridge Street in the Lower East Side, between Rivington and Delancey. The Play Street was focussed on the play of little girls in the dense low-income neighborhood. The city shut down the street and brought out two street pianos to play from 3:00-6:30pm. The New York Time’s July article says that the drivers and the push cart owners were happy to go around the Play Street. There was only one push cart owner who was not thrilled, and gave the police overseeing the event some attitude. (Note: In 1914, there was still some pushback from neighbors who did not want to be inconvenienced.)

The main attraction of the afternoon was a Rumanian folk dance by 14 year old Mollie Liebowitz of 86 Hester Street, which everyone at the Play Street loved. There were also dance instructors who taught the children some folk dance moves, and it was said that the little girls danced their hearts out til the end, and even protested when their time was up at 6:30pm. Sadly, the neighborhood boys did not want anything to do with the dancing, and so they planned to have a section that was devoted to play hockey at the next Play Street. The first Play Street was a huge success, and the New York times ended their article with, “So this afternoon the piano will play again on Eldridge Street.

The main attraction of the afternoon was a Rumanian folk dance by 14 year old Mollie Liebowitz of 86 Hester Street, which everyone at the Play Street loved. There were also dance instructors who taught the children some folk dance moves, and it was said that the little girls danced their hearts out til the end, and even protested when their time was up at 6:30pm. Sadly, the neighborhood boys did not want anything to do with the dancing, and so they planned to have a section that was devoted to play hockey at the next Play Street. The first Play Street was a huge success, and the New York times ended their article with, “So this afternoon the piano will play again on Eldridge Street.

By October 31, 1914 there were 21 active Play Streets that Police Commissioner Woods helped launch, and they began to multiply by the hundreds only a few years later. When Woods would walk by a Play Street in progress the children would stop playing and cheer for him. The mothers in the neighborhood started to create Mom’s groups. According to the New York Times mother’s told Woods that the Play Streets was one of the best things the city administration ever did to improve conditions for the moral and physical welfare of the boys and girls of New York City. The parents were so happy about the Play Streets, they created a fund to help pay a team of play teachers and play leaders.

By October 31, 1914 there were 21 active Play Streets that Police Commissioner Woods helped launch, and they began to multiply by the hundreds only a few years later. When Woods would walk by a Play Street in progress the children would stop playing and cheer for him. The mothers in the neighborhood started to create Mom’s groups. According to the New York Times mother’s told Woods that the Play Streets was one of the best things the city administration ever did to improve conditions for the moral and physical welfare of the boys and girls of New York City. The parents were so happy about the Play Streets, they created a fund to help pay a team of play teachers and play leaders.

“I expect to increase the number of Play Streets, so that in time practically all children of congested districts will be provided a place to enjoy themselves and safely play.” says Police Commissioner Arthur Woods.

We think it is important to know the rich history of the Play Streets movement. We are grateful for all of the New York City play advocates who believed in every child’s right to play safely and freely where they live among their neighbors. We stand on your shoulders, and will continue to encourage, support, and even fight for every child’s and every adult’s right to play. We believe play is here to stay!